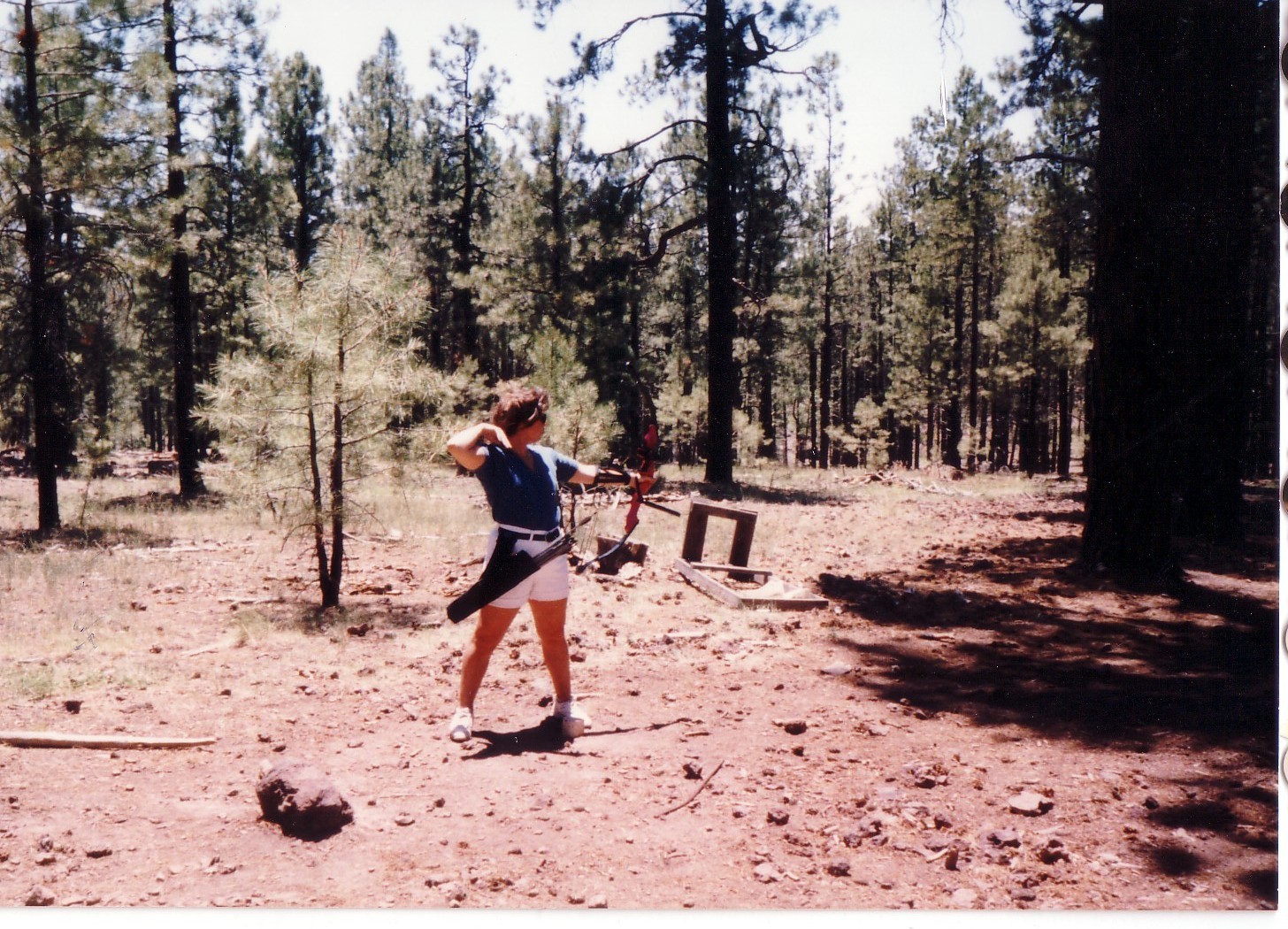

Years ago, I was heavily involved – nay, obsessed – with archery. With a strong draw and a good eye, I was (at one time) a fairly decent shot. I spent most weekends in 3-D competitions and most days in practice thinking about 3-D competition.

But I didn’t just start out as a good shot. It took a lot of hours and energy and preparation. I can’t even tell you how many times my forearm bore large black and purple bruises from a thousand pounds of pressure whipping across it when I released the arrow wrong. Or the hundreds of mornings I woke up with shoulders too stiff to move. Or the humiliation of missing more shots than I made.

Archery took years of practice, months of lessons, weeks of learning the equipment and hours of nursing painful injuries. To succeed, I learned to accept help from others who could see what I was doing wrong and who knew the sport. It took practice, hours and hours of practice.

I experienced equal parts of anger, frustration, patience and joy before I could confidently handle my prized hot-pink compound bow and bright blue recurve, a Hoyt Gold Medalist.

When you miss a shot in archery, you totally miss it. I’m not talking, “Oh, I just caught the edge of the target” kind of miss, I’m talking about wandering the desert for days, searching for an expensive carbon arrow (because when you pay in excess of $200 for a dozen arrows, you don’t want to lose it). You quickly learn that it is much easier to make the shot than it is to find (or worse, replace) an arrow.

One day, I was at my instructors home taking a lesson and I swear, for the life of me, I couldn’t group my arrows at 40 yards. No matter what the instructor told me to do, no matter how many sight adjustments I made, no matter how many times I walked over to retrieve arrows, I couldn’t create a tight grouping. The perceived distance was too great, my bow to weak, my draw too short. Since my instructor had a rule that we never end a session on a bad note, I knew I was in for a long day…

About an hour into the day, his six-year-old boy ran up next to me with a little toy practice bow that should never have been able to make a 40-yard shot, and quickly released three arrows without even aiming. Each arrow flew in perfect harmony, finding their places in the target to form a tight little group. It was like an archery angel had guided each arrow to its most perfect resting place on the target.

There was no sight or nock attached to this bow and he didn’t use a release (which I still consider to be a cheat).

I stood there watching him, my mouth hanging open in disbelief. As I watched him run off towards the target to collect his arrows, I finally choked out to my instructor, “How in the world did he do that?!”

My instructor shrugged and said, “He doesn’t know he can’t do it. We’ve never told him it’s hard to do, so he never grew up thinking there was a limit to what he can do. He doesn’t know it’s impossible. If you don’t know your limitations, you don’t have limitations.”

I’ll never forget those words because it was a turning point for me… I learned that nothing is impossible.

You’ll be told lots of things in life are impossible – whether it’s writing or archery or anything else. There are those who will say many things are impossible. But, in my opinion, those people lack vision. They haven’t envisioned the end result. And because of that, they lack the vision to make the impossible, possible.

As I matured, I learned that writing is a lot like archery. You have to practice every day. Sure, you have to know that there is a chance you will fail. You may very well have a great idea, but you could miss the mark and wind up wandering the desert for days. That’s okay. It’s all part of the lesson.

The important thing is that you return to pick up your bow and try again. You nurse that bruised arm, you find your lost arrow, you keep your bow tuned and your bow string waxed, and you try again.

All our lives, we’ve had people tell us certain things can’t be done. Writers are told that they can’t make money doing what they love. Artists are told there is no point in trying to sell their work because art is so subjective. Explorers are told there is no reason to explore because everything has already been discovered.

As a result, we think we’re not good enough. That we’ll never make it as a writer, artist, explorer, fill-in-the -blank. But, here’s the truth: people reflect their limitations onto us.

We are being told not our limitations, but the perception of another’s limitations. Limitations are merely externally perceived restrictions. And each time we hear those lies, we die a little inside. The more we hear it, the more some logical, scientific part of our innermost self begins to agree.

Richard Bach once said, “Argue for your limitations and sure enough, they’re yours.”

Just because something hasn’t been done, doesn’t mean it can’t be done. Don’t believe me? Ask Einstein or Edison. Van Gogh or Picasso. Shakespeare or Hemmingway. Think you can’t make a living as an author? Talk to Stephen King about limitations. Discuss breaking the rules of writing with JK Rowling.

Here’s the thing – don’t let anyone tell you can’t do something. Whether it relates to archery, writing, overcoming a physical issue, conquering your fear, or living your dream. Don’t let other people’s realities influence your reality. Know what you can do and do it.

Go ahead, take the shot…